|

|

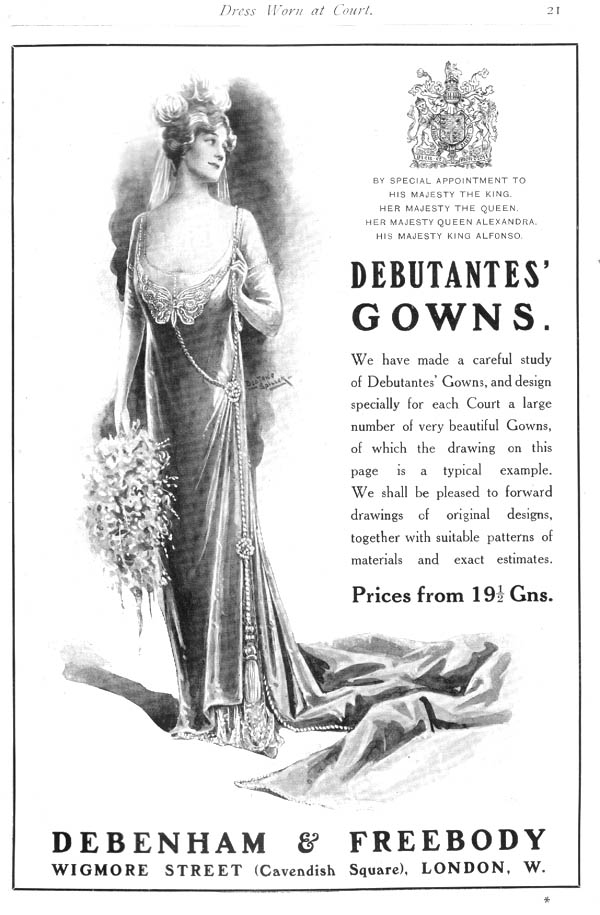

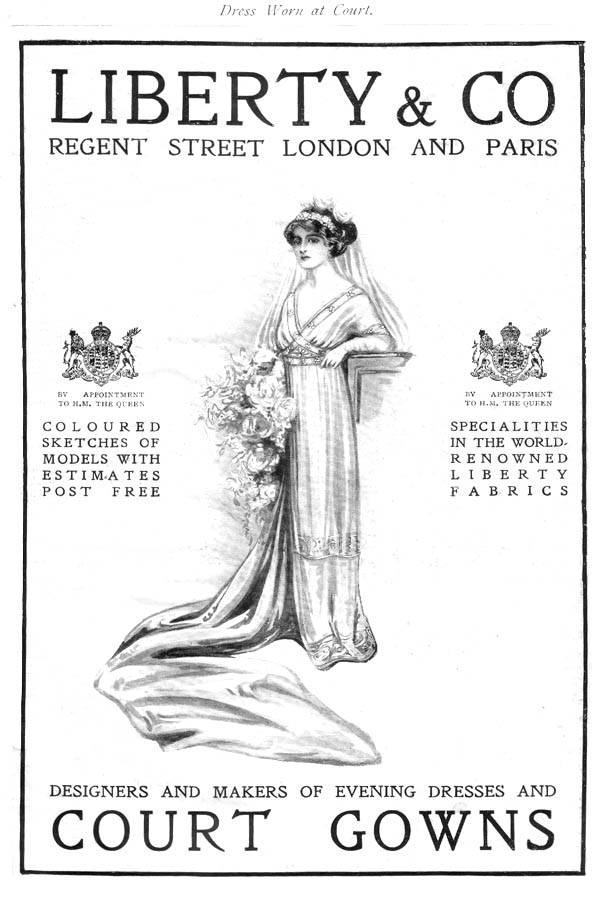

Debutantes

arriving in the Mall for presentation to Their Majesties at Buckingham

Palace [p 16]

|

|

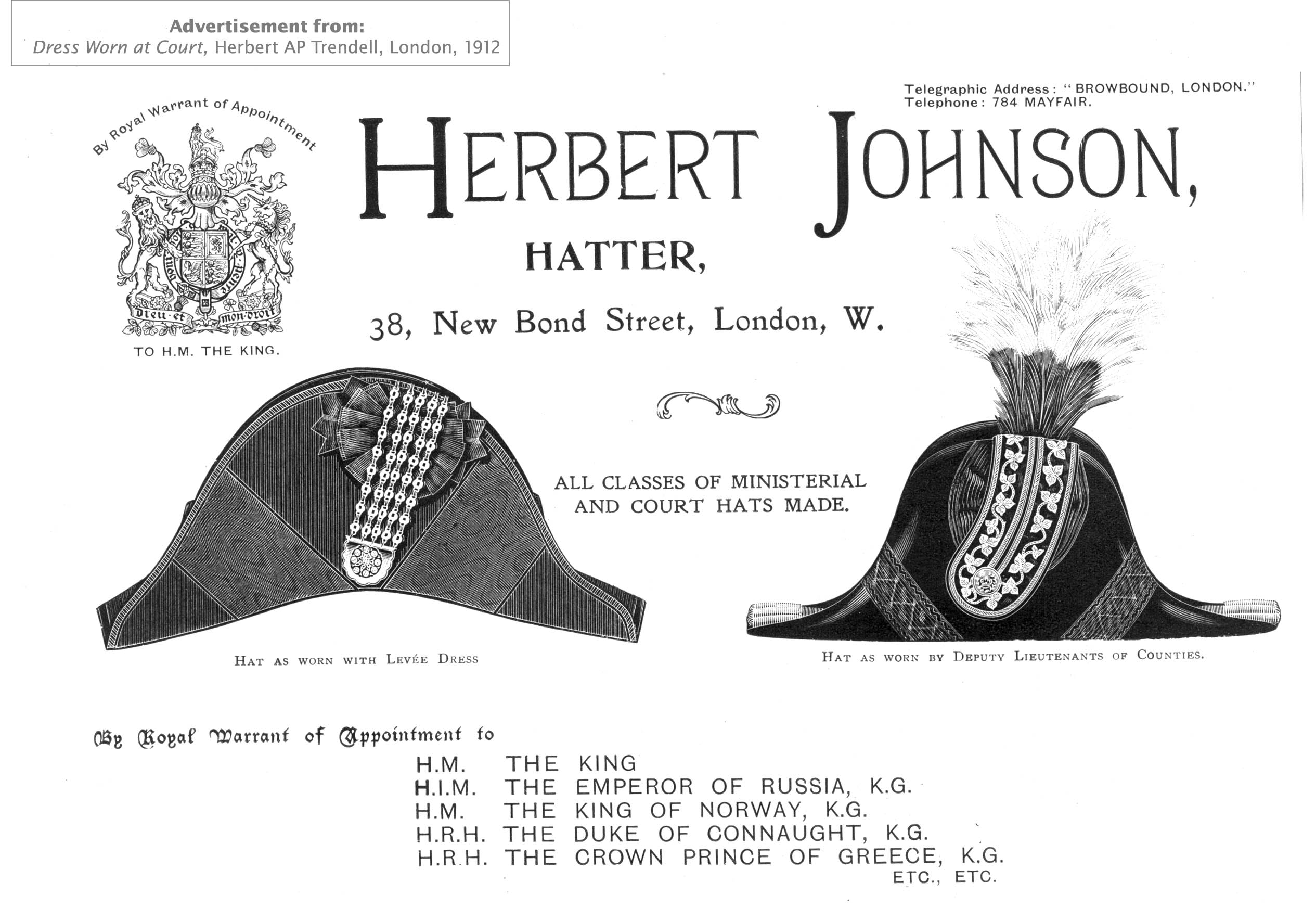

Janet Flanner, London was Yesterday 1934-1939, London, 1975 [from The New Yorker] [p 17] London is enjoying two novel states. It is sunny enough to have produced a rare water shortage: it has money enough to have created an evan rarer Season. For over a year, business in England has been taking aprofit; for less than a year it has been spending it. Their Majesties' Courts at Buckingham Palace are providing a climax for both. Four Courts are being held this year: two in May, two in pre-Ascot June. About six hundred ladies a night, or if you prefer, a total of twenty-four hundred females in feathers, are being presented. Around their curtsies, the customs of thousands of aristocrats and the commerce of millions of tradesmen rise in prosperous mutual motion. For England's budget is balanced, and with a surplus; sixpence is off the income tax. It is good news for any capital that the Empire's capital is again having good times. The protocol governing these Court-presentation costumes is perhaps the last strict social ruling on a lawless, changing earth. From Madame Elspeth Champcommunal of W. W. Reville-Terry, which, after generations of Court and Queen dresmaking, probably knows more about trains and feathers than anybody else except the Lord Chamberlain, come the following immutable facts: The King and Queen want gowns low and long, regardless of fashion; last year, stylish high-fronted numbers appeared. The King didn't like that. The Prince of Wales's three white ostrich feathers, plus a twenty-seven-inch white veil, must be placed on the head in the Ich Dien motto manner; are an order, not an arnament; are often handed down from duchess to granchild the worse for wear; and may, by special permission, be three black ostrich feathers in the case of a widow. The 1923 trains stretch eighteen inches back from the heel, are manteaux de cour, were four and a half yards long before the war, were cutt off entirely in postwar 1919, and the following year cut down to the present two and a half yards from the shoulder. (The extra-long queues of nouveaux riches, plus their fourteen-foot trains, were apparently more than the Queen could stand.) At Reville-Terry, the train's weight is distributed between shoulder hooks and stocking tops by a special net corselet, with garters, to prevent the gown from pulling back, or even off. Rehearsal of gown, shoes, feathers, fan, jewels, and curtsy are held in teh shop before the gown is delivered. Jewels are a great problem in Court-dress designing when fine family stones form the front of the frock. Court gowns must be flamboyant to show against hte Palace gilt, the Queen's blaze of diamonds, and the Royal Household uniforms; a mere chid Paris frock would stand no chance in Buckingham. Before entry to the Throne Room, trains are settled in place by attendants with long ivory poles. Curtsies have from time immemorial been taught by Miss Vacani; Truefitt or Douglas of Bond Street are still the hieratic hairdressers. A debutante is presented by her mother; after marriage, is re-presented by her mother-in-law. Court begins at 9:30 p.m. and ends around midnight, with supper after, the King's catering behind done by Lyons, the teashop people, and very good. This year's limousines and men-on-box are again

seen, both cars and servants in old family coach and livery colors. Last

year, motors of ladies Court-bound were for the first time allowed immediate

entry into the palace yard rather than kept waiting hours on teh Mall

- perhaps to relieve them of being admired by the unemployed. At any rate,

this year's unemployed have nothing to look at on Court nights at all. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|